Bernardo Bellotto: The Realist Who Stepped Out of Canaletto’s Shadow

Living in a Giant’s Shadow

Imagine trying to carve out a career as a painter when your uncle is literally the most famous artist in the world. That was the reality for Bernardo Bellotto (1722–1780).

His uncle was none other than Giovanni Antonio Canal, better known to history as Canaletto. Bellotto didn’t just share DNA with him; he was his student, his apprentice, and eventually his rival. He started training in Venice as a teenager, mastering the family trade so well that their work can be hard to tell apart at a glance.

But here is the trick to spotting a Bellotto: While his uncle Canaletto loved to bathe Venice in a warm, golden, idealized glow, Bellotto was a realist. He preferred a cooler, “silvery” light. His shadows are darker, his lines are sharper, and his water looks a little heavier. If Canaletto was the romantic poet of Venice, Bellotto was its high-definition photographer.

The Original "Instagram" of the 18th Century

To understand why this painting exists, you have to understand the Grand Tour. In the 1700s, it was a rite of passage for wealthy young British men to travel through Europe to “finish” their education. Venice was the ultimate party destination and cultural hub.

But cameras didn’t exist yet. If you wanted to show your friends back home where you’d been, you bought a vedute—a highly detailed view painting. These weren’t just impressionistic sketches; the buyers demanded accuracy.

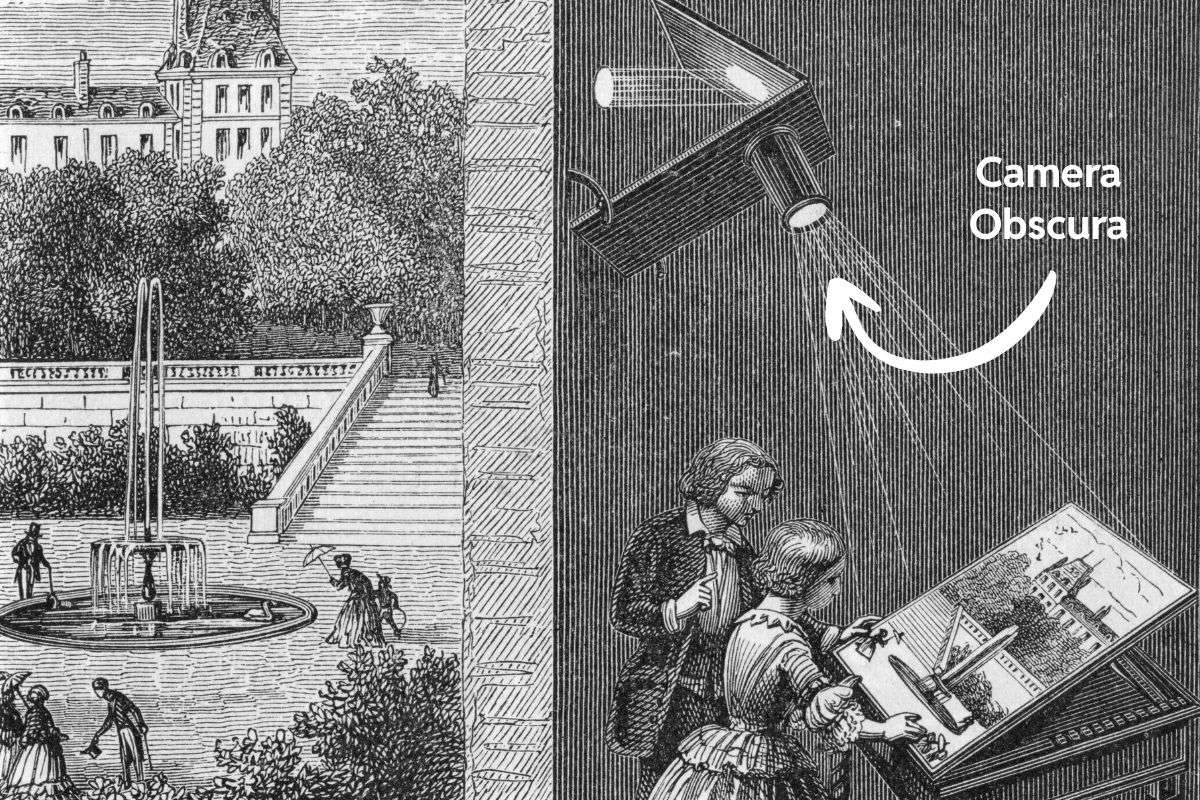

To achieve this photorealism, artists used a piece of technology called a camera obscura.

It was an optical device that projected an image of the scene onto a surface, allowing the artist to trace the exact perspective and outlines of the buildings. This is why the architecture in Bellotto’s work feels so mathematically precise.

A Deep Dive into the Masterpiece

In View of the Grand Canal, Bellotto flexes his technical muscles. He gives us a sweeping, wide-angle perspective that feels incredibly immersive. Here is what to look for:

The Architecture: On the right, the massive Baroque domes of the Santa Maria della Salute dominate the skyline. Just beyond it, you can see the Dogana (Customs House) topped with its golden weather vane. Bellotto paints them with such solidity you feel like you could reach out and touch the stone.

The “Bellotto Light”: Take a close look at the lighting. It is crisp, cool, and directional. Based on the shadows falling to the right, we know this is a morning scene, with the sun rising in the east. The deep shadows give the buildings volume and weight.

The Slice of Life: The bottom left corner is where the painting truly comes alive. This is the Campo (square), and it serves as a snapshot of 18th-century society. You can distinguish the classes by their dress—aristocrats in powdered wigs mixing with merchants and laborers. It’s not just a painting of buildings; it’s a painting of a functioning economy.

Why He Matters (The Warsaw Connection)

Bellotto is significant for more than just his pretty Venetian scenes. He was arguably one of the most important visual historians of his time.

later in his career, he moved to Warsaw, Poland, serving as the court painter. He painted the city with his trademark obsessive detail. Tragically, Warsaw’s historic center was leveled during World War II.

When the war ended, architects and city planners didn’t just rely on blueprints to reconstruct the Old Town—they used Bellotto’s paintings. His art was so accurate that it served as the blueprint for rebuilding a city from the rubble. He didn’t just paint history; he helped save it.

Both styles, though distinct, contributed hugely to the understanding of how art can reflect and elevate landscape imagery.

Other Works to Discover

The Fortress of Königstein (Series): After leaving the canals of Venice, Bellotto traveled to Northern Europe to paint massive, imposing fortresses. The shift from water to stone is dramatic.

View of Vienna: Here, he applied his precise Venetian technique to the grand imperial architecture of the Austrian capital, capturing the scale of the Habsburg Empire.